|

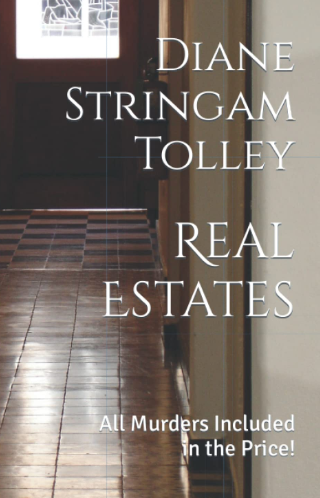

| The only surviving picture of Andrew |

Most of the time.

You get to spend your days outdoors, working in the pure, sage-stuffed air.

See the heat shimmer on the tops of hills.

Watch the prairie grass bend in the breeze.

You witness births and new life. See groups of calves, and sometimes their mothers, cavort and snort and play.

And see the milk cow try to run with the deer.

You can bury your face in your pony's thick, warm winter coat and just breathe in his 'horsey' smell.

You have long, wonderful talks with family members as you ride to or from.

And while you're working together.

It's a peaceful and serene existence.

And the scenery breath-taking.

But occasionally, it gets pretty gritty.

There are disasters.

Pain.

Death.

But even these can result in something beautiful.

Let me explain . . .

As occasionally happens, a young heifer (cow that hasn't yet produced a calf) was inadvertantly 'exposed' to a bull.

She caught. (Became pregnant)

But something went wrong.

Perhaps because she was so young. Perhaps because she had some physical and undetected abnormality.

Whatever the reason, she was dying and there was nothing that could be done to save her.

And her calf was just days away from being born.

My Dad had to make a quick decision.

He decided to take the calf early and then put the suffering mother out of her misery.

Fortunately, in times like these, a trained veterinarian can work very, very quickly.

One life saved.

Another let go.

And we had a new little bull calf.

An extremely healthy and active little bull calf.

I called him Andrew.

Because.

But Andrew didn't have a mama.

Normally, this doesn't present too much of a problem.

You simply adopt the calf onto another mama.

It isn't easy, but it's worth the effort.

Unfortunately, there were no 'mamas' available.

Bottle feeding was indicated.

Now any of you who have bottle fed a puppy or kitten or other young animal know that it's a time-consuming and constant thing.

Not so with calves.

They only need to be fed three or four times a day.

Fairly simple to work around.

And fun for the kids.

So we dug out our bottle and formula and gave our little man his first feeding.

He sucked strongly. A good sign.

On to the next hurdle.

Finding him a place to bunk.

Firmly rejecting our son's offer of his room, we decided on the corral.

There was only one problem.

The corral already had an occupant.

Old Bluey.

Bluey was an older appaloosa mare, gentle and slow.

Her mottled black and grey hair gave her a distinct 'blue' colour.

Thus the name.

Okay, so creative, we weren't.

Back to the problem . . .

We decided that Bluey probably didn't propose much of a threat to our little Andrew.

We carried the calf into the pen and set him down.

He stood there for a moment.

Blinking.

Then he spied Bluey.

Bawling loudly, he headed towards her.

She stared at this little apparition.

And moved away.

He kept on coming.

Again she moved.

This went on for some time.

Finally, deciding that Andrew would be all right, we left them together.

A few hours later, I took a new bottle of formula to our little orphan.

And received the surprise of my life.

There stood Bluey, with the calf beside her nursing loudly.

Nursing?

I should point out here that a horse is generally considerably taller than a cow.

Certainly, Bluey was taller than Andrew's mother had been.

In fact, to simply reach the mare's udder Andrew had to stretch as far as he possibly could.

But he was doing it.

And Bluey was letting him.

It was a miracle.

Another thing I should mention is that a calf is a lot rougher while nursing than a colt. Calves get very 'enthusiastic'. And if the milk slows down, they butt their head into the cow's udder.

Not so with colts. They are quite gentle. Even mannerly about their feeding.

I probably needn't point out that Andrew was a calf.

And an extremely enthusiastic one.

I watched as he butted his head into Bluey's udder. I could almost feel her wince.

She raised her leg and closed her eyes for a moment.

Then she lowered her leg and let him nurse again.

It truly was an amazing sight.

Throughout the summer, between bottle feedings, Bluey nursed Andrew.

Once, we left the calf in the corral and took Bluey out to bring in the herd, intending to capture them in that same corral.

As we drew close with the herd, someone opened the gate.

Little Andrew came running out, searching for his 'mother'.

And bawling loudly.

Bluey nickered back at him anxiously and he quickly found her and took up a position at her side, following along happily.

Eventually, in the fall, all the calves were weaned, taken from their mothers and put into the feedlot together.

For a day or two, there was a lot of bawling and angst.

Then they discovered the feed troughs.

And discovered, too that they had very short memories.

Peace was restored.

Bluey, too, resumed her peaceful life as though it had never been interrupted.

There is an addendum . . .

I checked Bluey's udder once while she was with her little adopted boy.

She had no milk.

None.

She had done all of that 'Mothering' with an empty udder.

The pain must have been exquisite.

But she did it.

Cheerfully.

Yep. Definitely a gold medal performance.